Man, This is Fun

Based on the current state of my Netflix queue, it appears that I'm drawn to documentaries about people that have spent most of their lives doing one thing.

I know that I'll be a photographer for the rest of my life -- regardless of how the medium, and the business changes -- and that I'm committed for the long haul. I've traveled far enough down the visual creative road that I'm not really interested in turning back. Im in, whether I like it or not.

I saw in the NYT recently that Gerhard Richter's 1994 painting titled "Abstraktes Bild (809-4)" just sold for $34M -- the highest amount ever paid for a work by a living artist. Eric Clapton paid just over $1M for the same painting in 2001:

Not a bad return.

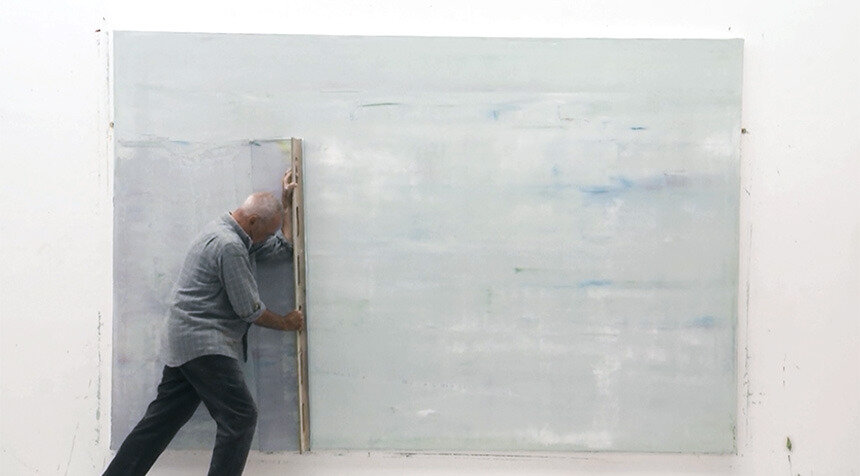

What's it like to be 84 years old, and to be regarded as one of the greatest living painters in the world?Gerhard Richter Painting attempts to answer this question.

There are long, quiet shots of Richter painting in his gorgeous studio, as well as a few openings and press conferences in legit museums and galleries -- mostly in the presence of well dressed, creatively bespectacled art scene types. Richter's statements about his work, and about painting in general, are elusive, hazy, and open-ended, much like his work, which seems to resist classification. He seems like he's tired of answering the same questions about his work, as if he's explained himself so many times that if people don't get it by now, then screw 'em.

His 50+ year career has moved from photo-realism to abstract, portrait to landscape, and everywhere in between. By simply continuing to work, year after year, he continues to evolve and elevate his work. According to his crazy website, where all of his work is categorized in a fully searchable database, he has completed 3,531 paintings since 1962.

I loved watching Richter paint. Whether he was wielding a heavy, overloaded brush, or pushing his massive squeegee across the canvas, I kept trying to connect his head to his hand, to translate his actions.

What made him swirl the brush at that particular point? Why did he start on the right side of the canvas instead of the left? What made him stop and step back, then scrap the whole thing and start over?

Most likely these are questions that Richter himself couldn't even answer. At this point he has literally become his craft, and the brushstrokes and squeegee smears are just happening on their own. If he steps back and looks, and doesn't like what he sees, he pushes on. This small instance of covering a brushstroke, or an entire painting -- and pushing on toward something that feels right -- is his entire career.

Paint, step back, look, fix, repeat.

My favorite scene from the film: Richter has slathered a huge squeegee with several pounds of paint, and is pushing it across the canvas, from left to right. The squeegee moves slowly, then gets bogged down and is stuck. Richter can't get it to budge. So he shifts his weight, bears down and puts his shoulder into it like a lineman, muscling it through to the other side.

There was something so simple and beautiful about this moment that it actually made me cry. (Not like sobbing and tissues cry. Just a few happy little tears.) Partly because in that moment I could feel how he was one with his work, and partly because that's where I want to be when I'm 84.

Richter then closes the film perfectly with a short, sweet line -- "Man, this is fun."