Into the Rabbit Hole

A few months ago, I wrote about my recent trip to British Columbia, where while crossing a glacier, I had a “vision” of a form. This led to a visual exploration of this form — I started sketching it, making prints of it, then eventually drawing it digitally so I could iterate it more quickly. I wasn’t sure what I was chasing, but I was curious to see where the search might take me.

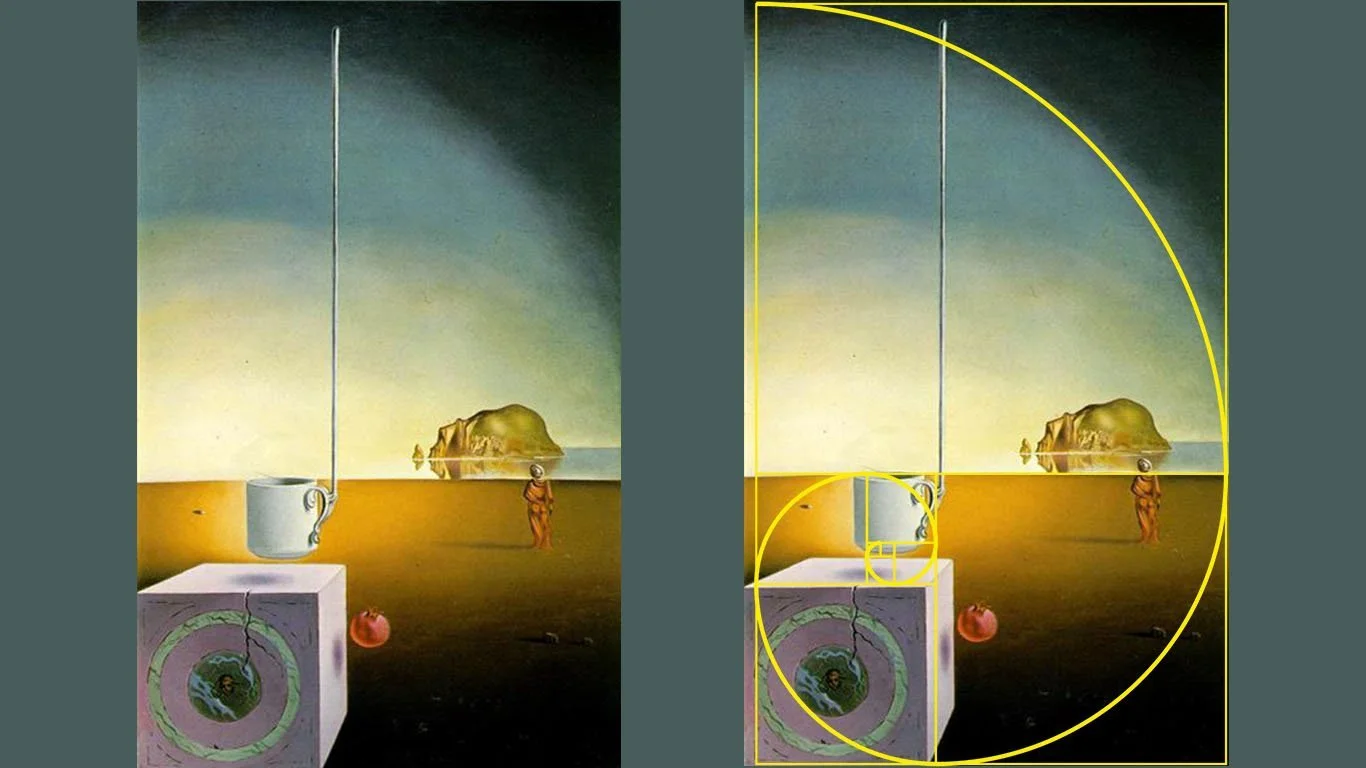

The form that appeared in my mind that day in BC was a variation of the “Golden Ratio” which is something I have always known about. My basic understanding of it was as a ratio that appears widely in our world — showing up in plants, animals, human anatomy, as well as in ancient buildings, famous artworks, etc.

In mathematics, two quantities are in the golden ratio if their ratio is the same as the ratio of their sum to the larger of the two quantities. Known to mathematicians as “phi” or “Φ” the result of this ratio is a number that looks like this:

Φ = 1.618033988749895...

As an irrational number, it goes on forever. And visually, it looks like sort of like this:

This idea of one number to provide a blueprint for the natural world makes sense to me - that nature would eventually default to some ratio that just worked better than others for a variety of reasons. It could be to attract a mate, or to provide some other subconscious visual appeal in order to propagate life through incremental gains in evolution and longevity.

The Golden Ratio seems to have taken on a sort of mythical quality. It’s a concept that bridges the worlds of science and nature in a way that provides a clear framework for our understanding of and connection to our natural surroundings.

The Greeks used it to build the Parthenon, Salvador Dali used in his paintings, Le Corbusier designed it into his buildings. And I have to admit, I fell for the simple elegance of this explanation. Over many years, I applied it to photographs, saw it in places it may or may not have existed, and generally gave this magical number of 1.618… the benefit of the doubt. I even designed and manufactured a clock based on its proportions. Even if I couldn’t physically see it in nature, I could feel its existence. There was comfort in knowing that this magical number was baked into the core DNA of everything and everyone around us.

After my experience in BC, I spent several months visually exploring this concept via photography and illustration — repeating and iterating, following that golden spiral inward as it got smaller and tighter, but never actually closing. Eventually I decided to look more closely at the actual science behind this mysterious little ratio. And sure enough, the existence of the Golden Ratio in our natural world is not as clear as some may think, although there is certainly some beautiful truth to it. For instance, pineapples and artichokes have a spiral growth pattern that relates directly to the Fibonacci sequence, which is a close cousin of Φ. Pretty cool. There are committed believers dedicated to a showing us a whole lot of ways that the Golden Number exists in our world. In some instances, math and nature sync up perfectly, which is quite beautiful. There are also a lot of opposing sites dedicated to debunking the Golden Myth.

I’m not going to pick sides, but I am more inclined to think that our tendency to see this ratio all around us is not as accurate as we may believe. Our brains have a basic neurological need to find patterns in our surroundings, a phenomenon known as “apophenia.” Back when survival was a daily life-or-death concern, this skill would help us to recognize prey or avoid eating poisonous plants. Our hard-wired inclination to see patterns helped us to stay alive. These days, we’re spending less time hunting and gathering, and more time staring at screens and drinking beer. Which probably explains why cars, houses, and other inanimate objects can sometimes look to us like faces:

Around the same time, I was reading Art in the After-Culture by Ben Davis, an excellent book that really encapsulates the time we are in — politically, socially, and artistically. Davis states, “It is a scary and disorienting time for art, as it is a scary and disorienting time in general. Aesthetic experience is both overshadowed by the spectacle of current events and pressed into new connection with them. The self-image of art as a social good is collapsing under the weight of capitalism’s dysfunction.”

Conspiracy theories exist because they help us explain the unexplainable. They give us comfort and security and clear answers in the face of chaos and uncertainty.

Through Ben’s book, I was led to a NYT podcast called Rabbit Hole, which explores how and why some conspiracy theories get traction. The host of the show, an NYT reporter, follows the path of a young educated guy and his intricately detailed YouTube viewing history to chart his gradual conversion to far-right conspiracy theorist. Eventually he comes to see that he is deep in a dark, twisted rabbit hole, and climbs out, only to be algorithmically catapulted across the spectrum and into another deep, far left abyss of extreme ideology.

This really hit home for me, and provided an interesting lens through which to look at the world. Our current techno-social-political system is one designed to efficiently coax people into these rabbit holes, where they become so entrenched in their beliefs that things like science and facts and general common sense are less valued, if at all. Trying to convince the zealots of anything different than what they believe just makes them double down and dig in even deeper.

This naturally made me wonder what my own blind spots are. What is my belief system and where did I get it? Was it even my own choice — or am I another pawn in the continuing algorithmic polarization of our society? Isn’t the New York Times just another capitalist system that profits through this polarization? Am I truly open to other perspectives, or even multiple perspectives at once? Am I capable of clear, unbiased discourse with someone from “the other side?”

I thought back to the Golden Ratio. Is this an example of a (relatively harmless) conspiracy that I had fallen for? Its simple elegance certainly provided me some comfort in a visually chaotic world. Without questioning it much, I just believed in it. I used it to inform and influence my work. I didn’t bother to look at the facts or read the science because it was a convenient system. I had been coaxed into a rabbit hole of my own, a realization that was ultimately revealed by artistic exploration and a general sense of curiosity.

Is this happening to me in other parts of my life? How? And for how long?

As Davis, says in Art in the After-Culture, “I think it is very important, as a first step, to be able to see your own reflection in conspiracy theory. I also think that doing this risks — and requires — a sense of obliterating your own self-image as separate, better than, and so forth. If you cannot understand it, on any level, then you will be hard pressed to to counter its appeal. Then all you are left with is your own form of delusional belief and your own form of magical thinking.”

I also found it really interesting that the Golden Ratio in visual form looks a lot like an actual rabbit hole — it’s just spirals down, getting deeper and darker, but never quite ending.

Coincidence? Or Conspiracy???