Back to Analog

The day I enrolled at the San Francisco Art Institute, I bought a Hasselblad 501. As a student, I got great pricing, and after many years of 35mm SLR’s, I was eager to finally own that beautifully timeless chunk of Swedish photo goodness.

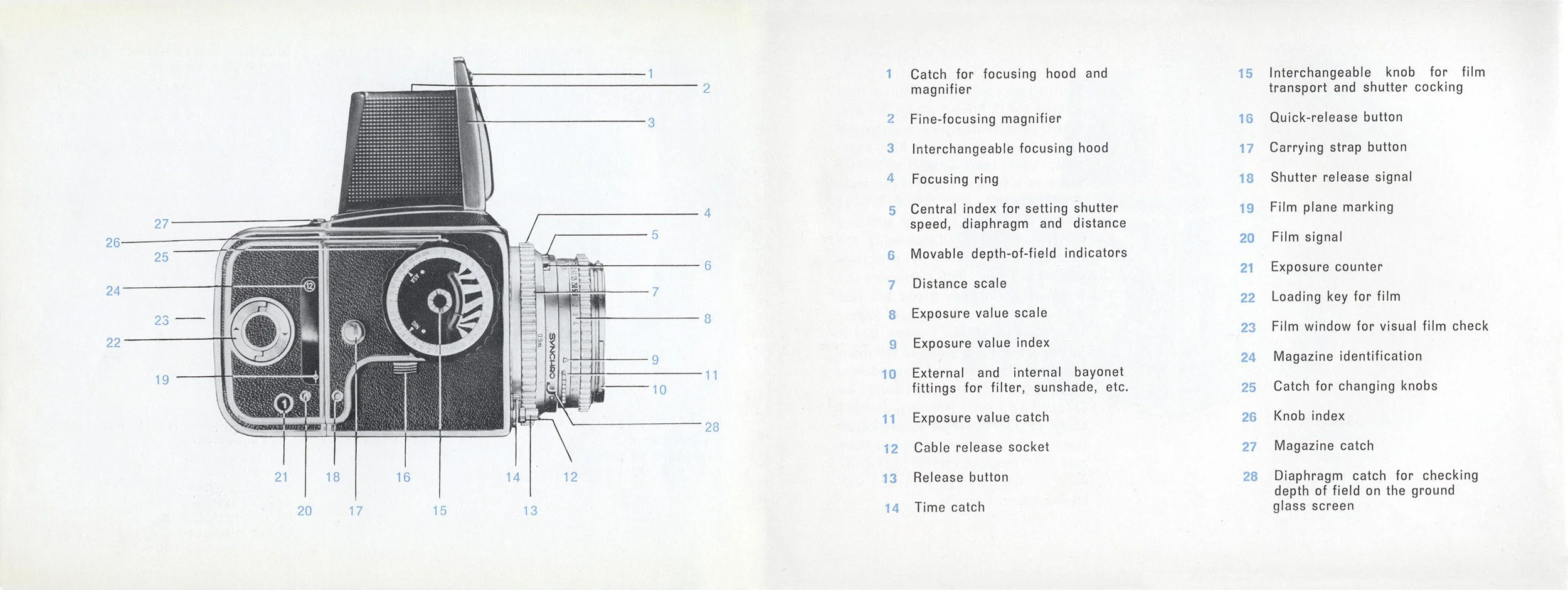

The 120 film that the Hasselblad gobbled up was bigger and more expensive, but it was so much more impressive than 35mm film. The images had a new depth and detail that I loved. The camera was fully mechanical, so loading and focusing and shooting and winding and shooting some more and unloading required manual precision, and was by no means foolproof. Exposing the film properly required keeping a good light meter handy (Sekonic, ftw) and knowing how to use it.

The whole process called for intense attention to detail, calling on every ounce of your hands, eyes, and brain. The top-down viewfinder flipped the image that you’d see when you looked through the camera — left is right and right is left — which would make your brain backfire, until it rewired itself. The camera couldn’t beep at you if your image was underexposed, or if you had no frames left on your roll of film, or if the frame was out of focus. To shoot professionally and get paid, you had to know your shit, technically. Very well. If you didn’t, you’d pay for it, eventually.

Going to The New Lab to pick up developed film was always a blast. After chatting with the regulars behind the counter, or running into other photogs, I’d take my film to the nearest light table, grab a loupe, and start looking through everything, drawing little Sharpie stars in the top right corners of my faves. Then, I’d carefully cut the 12 frames into separate pieces of film and slot them into 3w x 4h sheets, which would then go into a binder.

Inevitably, photography started shifting over to digital. It was slow at first. The first camera I owned was a 2 Megapixel Nikon. But it wasn’t long before film cameras faded away, and my trusty Hasselblad was on the shelf, gathering dust. Not because I didn’t love it — there was just no denying the power and efficiency of a digital camera when trying to make a lot of images quickly. When shooting digitally, agency creatives and clients could know immediately that they “had it,” instead of hoping they “had it,” then having to rely on the photographer to assure them that they “had it,” then wait a day for the film before they’d know for sure they really had it.

The new digital cameras were good, and getting better. They knew if your image was underexposed, or if you were on your last frame. They would warn you when your card was close to full, and track moving objects better than any human. The RAW format allowed you to be careless about exposure, as it provided a huge cushion of digital latitude that was way beyond the capabilities of film.

The megapixel arms race began, in the search for more and more resolution. The gear got really good, and eventually, it got really expensive. The cameras got smarter, and latitude and low light performance got even better. Pretty soon all you had to do was pick up a decent camera, point it at something, blast a bunch of frames, and technology would take care of the rest. It was pretty hard to screw up the technical part.

Over my many years of being in this increasingly digital workflow, I’ve always tried to balance it with activites that are more analog and outdoors, with bicycles being one of my favorites. I’ve never had a computer or power meter on my bike, and I’m not planning to get an e-bike anytime soon. (Rudy, if you’re reading this I’m going to win our bet).

As technology accelerated, my digital camera started to feel like a limiting factor, instead of a useful capture tool. The contents of a single photograph are largely determined by the physical world that exists in front of the lens. Of course, it’s pretty easy to come up with a cool idea for a photograph, but making that image into and actual photograph can be insanely complex and difficult, since subjects, laws, permits, and physics often stand in the way.

As the limitations of lenses and optics became more and more apparent to me, and the camera started doing more and more of the technical stuff, I started pushing in the opposite direction, combining and manipulating images. I started layering and cutting and tweaking to make images that didn’t resemble anything in reality, let alone an image that a camera could even capture.

Gradually, “straight photography” — shooting a single, unedited image — became less interesting to me. I wanted to make photographs that looked like lithographs, screenprints, or paintings.

I was more into Diebenkorn:

And less into Gursky:

A camera is a great tool if you’re into Gursky. But I was drawn to graphic fields of color, clean lines, and simple compositions that were less about capturing a moment, and more about capturing a feeling. At times, the camera didn’t seem like such a great tool for the images I wanted to make.

So when I finally did a printing workshop at Anderson Ranch, it felt like I’d discovered what I’d been looking for all along with my camera. There were no lenses or shutters or sensors or beeping alerts to get in the way.

Since then, it has taken me a minute to get my new studio built, and to start a clock company (analog of course). But as the proud new owner of a Conrad Etching Press, I have been making prints every week since it showed up last summer.

Working with the Conrad is a delightfully manual process that, if you want to achieve clean color fields and crisp lines, requires pretty serious attention to detail. It’s a simple machine that does one thing really well, but it won’t beep at you if you’re doing something wrong. And, like shooting film through a mechanical camera, you get one shot. The way I’m working is known as “monoprinting” because you can only run the image through the press once — there’s no cranking out reproductions here — it’s one and done. So everything I’m making now is 1/1 and needs to count. Which demands a level of manual focus that I appreciate.

In a way, I feel like I have come full circle back to my old Hasselblad — working with a beautifully made tool that demands full focus and technical skill. Each week, the prints get a little better, and I get a little closer to having the prints match what I have in my head:

I haven’t picked up my camera in months. And for now, I’m ok with that.